Celebrate Black History Month: Charles R. Drew

Charles R. Drew was an African American physician and medical researcher who developed the world’s first blood bank as well as contributing improved techniques for blood storage and transfusions. Drew was also outspoken against the practice of racial segregation in blood donation because it lacked any scientific foundation.

Drew was born in 1904 to a middle-class black family in Washington D.C. After attending Amherst College in Massachusetts, he attended medical school at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. There, he distinguished himself by winning the annual scholarship prize in neuroanatomy, staffing the McGill Medical Journal, and winning the J. Francis Williams Prize in medicine after beating the top 5 students in an exam competition. Drew graduated second in his class in 1933.

Drew won a fellowship to train at Presbyterian Hospital in New York in 1938 while earning a doctorate at Columbia University. Drew was assigned to work under John Scudder, who was granted funding to set up an experimental blood bank. Drew and Scudder focused their research on diagnosing and controlling shock, fluid balance, blood chemistry, preservation, and transfusion.

This work led to his seminal dissertation, "Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation." His thesis focused on plasma which, being devoid of cells, could be given to anyone in need, regardless of blood type. He also devised a method by which plasma could be dried and then reconstituted with distilled water later on when needed. The two innovations would transform emergency medicine. He became the first black person to earn a medical doctorate from Columbia.

In late 1940, the U.S. developed the relief program Blood for Britain which aimed to collect and ship plasma overseas. Drew became the medical director for this program and instituted uniform procedures and standards for collecting blood and processing blood plasma at the participating hospitals. He created bloodmobiles that contained refrigerators of stored blood, a central location for blood donation, and made sure all blood plasma was tested before shipped out. The Blood for Britain program operated successfully for five months, with almost 15,000 people donating blood and over 5,500 vials of blood plasma.

Having established himself as the leading expert in blood donation and banking, Drew was appointed director of the American Red Cross Blood Bank pilot program in 1941. He withdrew from the program after the armed forces ruled that the blood of black people would be accepted but stored separately from blood collected from white people.

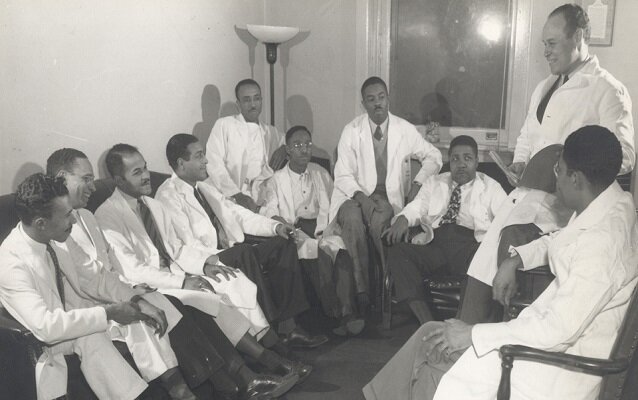

For the next nine years, Drew served as the Head of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at Freedmen's Hospital at Howard University. His mission was to “train young African American surgeons who would meet the most rigorous standards in any surgical specialty” and “place them in strategic positions throughout the country where they could, in turn, nurture the tradition of excellence.” This he believed would be his “greatest and most lasting contribution to medicine.” He also campaigned against the exclusion of black physicians from local medical societies, medical specialty organizations, and the American Medical Association.

Charles R. Drew died in a car accident on April 1, 1950, while driving to a conference.